Deutsche Bank on the Wrong Track (But on the Right Path?)

There is an episode in the early history of Deutsche Bank that reminded me of their more recent entanglement with Donald Trump and their willingness to lend vast sums of money to imposters and fraudulent characters when they should have known better.1 Yet the story takes a surprising turn that subverts impressions of a bank whose recklessness in our own time appears, at first glance, to be reflected in events that transpired over a century ago.

It is a tale about two men with different backgrounds but also many similarities: Georg von Siemens, a Deutsche Bank manager, and Henry Villard, an American railroad tycoon, born in Germany as Heinrich Hilgard. Among their similarities was an apparent lack of interest in financial details combined with a passion for America's potential.

Georg von Siemens was one of the first directors of Deutsche Bank and the most influential character behind the bank's early expansion. He was considered the principal driving force and creative mind behind the bank’s development during its first 30 years. Deutsche Bank was founded in 1870 with the main purpose of supporting German overseas trade. The newly established bank was supposed to make German exports more independent from London’s banks, which dominated trade finance throughout the 19th century.2 But from the very beginning, Deutsche Bank also ventured into other areas such as industrial financing, the deposit business (which was dominated by savings banks at the time), and investment banking. In some cases, the bank even assumed an entrepreneurial role, as in the famous case of the Baghdad Railway.

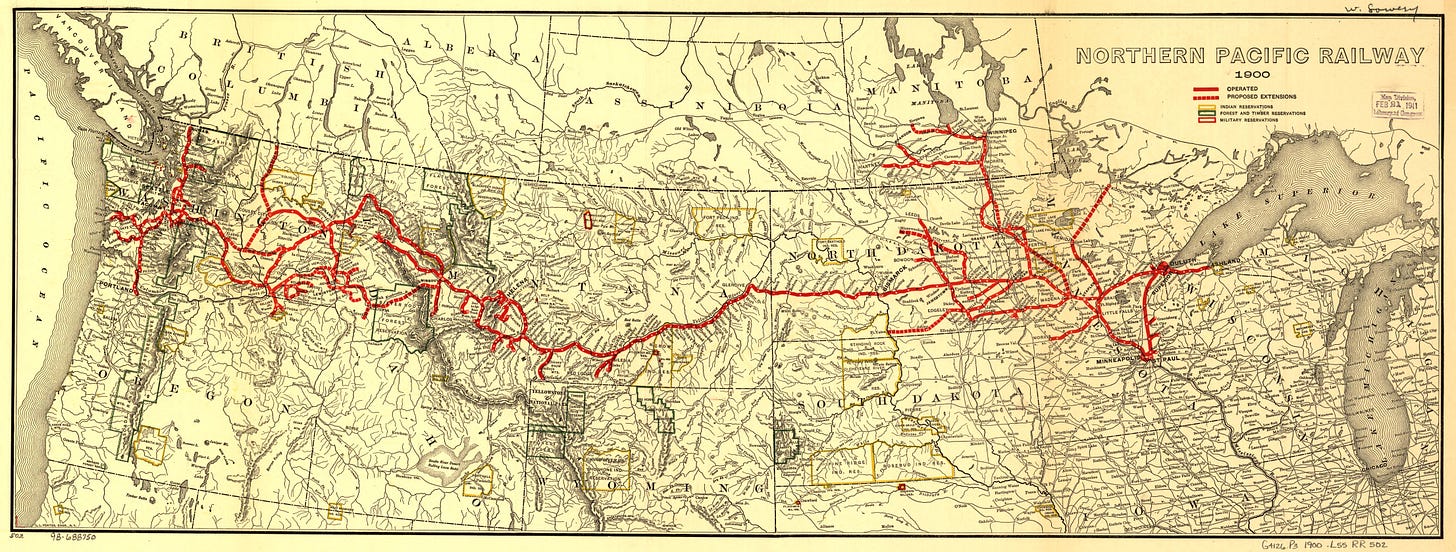

This story, however, is about another railway and predates Deutsche Bank's adventure in the Middle East. It is set in the United States of America, primarily during the 1880s, and involves the Northern Pacific, a railroad company that, according to Kobrak (2008), “enjoyed one of the most turbulent histories in a sector full of such stories.” It was during the 1830s that the construction of transcontinental railroads slowly began to kick off in the United States. The interest of German investors in American rail projects had already been awakened by the beginning of the 1850s (Seidenzahl 1970). During the 1870s the demand for funds from foreign investors reached new heights.

Siemens saw the huge economic potential of the United States. He wanted Deutsche Bank to share in the profits that were expected to materialize on the North American continent. While he was certainly right about the economic potential, he also underestimated the problems and complexity of railroad investment, as did many others. When he received an invitation to the grand opening of the Northern Pacific railway line in 1883, Siemens immediately agreed.

It is at this point that Henry Villard comes into play. I first read about Villard and the Northern Pacific in Lothar Gall’s essay on Deutsche Bank's history from 1870–1914. He describes Villard as “a man who, with his personal charisma and skillful publicity [...] was able to mobilize more and more funds, while his company was actually on shaky ground.”3 As president of the Northern Pacific, Villard “wanted to win new investors for the company on the way to the opening, which was staged with great pomp, because at this point the precarious financial situation of the company was already well known.”

The shares of Northern Pacific lost half of their value while Villard was still celebrating the opening as Wall Street realized – and here I defer to Wikipedia, because they nailed it – “that the Northern Pacific was a very long road with very little business.” While Georg von Siemens was already – more or less – aware of the financial difficulties of the Northern Pacific, he decided to invest anyway. He seemed to believe that a consolidation of the company was possible and would bolster immensely the international reputation of Deutsche Bank.

Deutsche Bank bought up a large number of subordinated securities to sell to their German clients. As the Northern Pacific’s financial crisis worsened, Deutsche took up another sizable chunk of second lien bonds. At the end of 1883, Villard was forced to resign as president due to a loss of confidence in his ability to remedy the company's mounting financial problems.

Henry Villard went back to Germany to stay with his family and wait for another opportunity to return to the United States. This opportunity came in 1886 when Deutsche Bank, which had decided to take the next step and invest in equity of the Northern Pacific, found themselves in need someone to improve the flow of information about the company and to protect their interests. After being reintroduced to Villard by another Deutsche Bank manager, Siemens regained trust in him and decided that he would be the one to represent the bank's interests in North America. Or, as Villard’s great-granddaughter put it:

“Armed to the teeth with German capital, Henry Villard could return to the railroad wars.”4

In 1893 a financial crisis became the straw that broke the camel's back and led to the Northern Pacific’s second bankruptcy.5 Henry Villard left the company, blaming everything and everyone but himself.

The German investors who bought Northern Pacific securities from Deutsche Bank obviously lost a great deal of money. But here is, where the story takes an interesting turn. Georg von Siemens took the failure personally and was shattered and ashamed by the outcome of his venture. As he felt responsible, he decided to use a large part of his personal fortune to buy back shares from disappointed German investors who had purchased Northern Pacific bonds and shares on his advice (Gall 1995; Kobrak 2008). At least in this case, Siemens was the morally responsible and personally liable “good banker” similar to George Bailey in the movie It's a Wonderful Life.

On Villard

The depiction of Henry Villard above is heavily influenced by Lothar Gall’s essay on the early history of Deutsche Bank. He is mentioned only briefly, but as I have written above he immediately reminded me of Donald Trump. Of course, when I thought about writing down this story, I had to do a little bit more research. The first website I found on the subject of Villard was the Oregon Encyclopedia, which described him thus:

“For Oregon, he is best remembered as the man who brought the first transcontinental railroad to the Northwest in 1883, connecting Oregon to the rest of the country. He sponsored several trend-setting buildings […] in the region and was instrumental in rescuing the University of Oregon.”

One can’t deny that it is also largely to his credit that the railroad connecting large parts of the Northwest with the rest of the United States was finished so quickly. In this respect, it was probably even helpful that he deceived foreign investors by not paying in full what the Northern Pacific owed them. Some of the railroads might not have been profitable without foreigners bearing a portion of the costs. This clearly explains, why, from the Oregonian point of view he is seen in a much better light. The irony is that Villard was originally chosen by a Frankfurt committee to protect the interest of German investors in the United States.6

Together with Deutsche Bank, Henry Villard was also heavily involved in the projects of Thomas Edison and the electrification of the United States. As a matter of fact, thanks to Villard’s close relationship with Edison, Georg von Siemens and Deutsche Bank were able to play a central role in American-German business relations, the exchange of capital and patents between these countries and even in the electrification of much of the world (Kobrak 2008). But that is another fascinating story involving AEG, General Electric, and Siemens & Halske AG, the latter of which would later (together with two other companies) become today’s Siemens AG.7

Thus, it would seem that comparing Henry Villard to Donald Trump is a bit unfair after all, despite some obvious similarities.

References

Boyd, W. H. (1946). The Holladay-Villard Transportation Empire in the Pacific Northwest, 1868-1893. Pacific Historical Review 15 (4), 379–389.

Enrich, D. (2020). Dark Towers - Deutsche Bank, Donald Trump, and an Epic Trail of Destruction. HarperCollins Publishers.

Gall, L. (1995). Die Deutsche Bank 1870-1914. In: Lothar Gall et al., Die Deutsche Bank 1870 - 1995, pp. 1–135. C.H. Beck.

Kobrak, C. (2008). Banking on Global Markets - Deutsche Bank and the United States, 1870 to the Present. Cambridge University Press.

Seidenzahl, F. (1970). 100 Jahre Deutsche Bank. Deutsche Bank Aktiengesellschaft.

Xu, C. (2020). Reshaping Global Trade: The Immediate and Long-Run Effects of Bank Failures. Proceedings of Paris December 2020 Finance Meeting EUROFIDAI - ESSEC.

If you want to read more about Trump and Deutsche Bank, I recommend Enrich, D. (2020). Dark Towers - Deutsche Bank, Donald Trump, and an Epic Trail of Destruction. HarperCollins Publishers.

Xu (2020): “At the time, Britain was the center of the global financial system, and British banks operated in countries that accounted for 98% of world exports, while providing over 90% of trade finance globally.”

My own translation from Gall (1995)

Found in Enrich (2020)

Kobrak (2008, p.65) “The receivership of the Northern Pacific in 1893 was part of the third great spike in American railroad bankruptcies of the nineteenth century - the first two came in 1873 and 1884, falling at ten-year intervals but with different durations. In 1893 alone, an astounding 74 rail companies with $1.8 billion in capital and 30,000 miles of track went into receivership, nearly one-sixth of America's 1890 rail capacity and nearly as many miles of track in one year as during the prior nine years combined.”

See for example Boyd (1946): Henry Villard “undertook to salvage investments of German creditors in the Holladay enterprises.” Boyd also even describes Villard as “an organizing genius” whose policies “combined enthusiasm and energy. However, Boyd’s paper seems to be heavily influenced by Villard’s autobiography.

Kobrak (2008) has an excellent chapter about “Deutsche Bank and American Electrification.”